PIAAC data cover all formal and non-formal education activities (either work-related or non-work-related) carried out by respondents (except 16-24 year-olds who are in their initial study cycle) in the 12 months before the survey.

Adults participation rate to training activities is the lowest among PIAAC participant countries, 24% vs 52% OECD average. A significant majority of them are employed (81%).

Respondents embarked on training mainly with a view to improving some work issues, and training was carried out mostly outside working hours, in case of a formal training, or mostly within working hours in case of a non-formal training. It’s generally perceived as useful for the job performed (the percentage resulting lower in case of formal training: 67% vs 86%).

Major hindrances to participation (and hence the major work-life balancing issues) were related to job commitments (more in the North and Centre regions compared to the South and Islands), followed by family care issues (in particular for women), and attendance costs (more frequently in the South compared to the North and Centre regions).

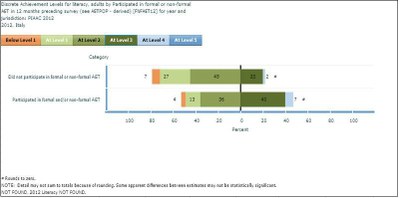

Those who had previously participated in training activities quite clearly achieved higher skill levels (even more so in case of formal training) at proficiency tests: the percentage of those who achieved level 3, which is considered as the current threshold level to live and work effectively, or above, is twice as much (see following chart) with the average score going from 241 to 268.

Participants and non-participants in education and training activities per skill level (literacy)

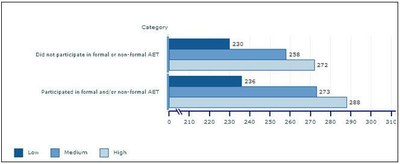

Under equal levels of education, participation in training activities provides a performance advantage which appears to be stronger as regards levels of education going from school-leaving certificate up and less strong for those with low levels of education (see following chart).

Performance of participants and non-participants in education and training activities per level of education [1] (average literacy scores)

Participation in training activities significantly helps to maintain skill levels in time: individuals over 55 with training experience have much higher skill levels compared to non trained peers, and generally above the Italian average.

Learning boosts the desire to learn: 49% of the unmet demand for training is from people who have already participated in training activities over the last 12 months.

Those who reach the highest skill levels are much more likely (more than twice as much) to participate in training activities, compared to those with low skill levels.

Therefore, if for high-skilled workers the envisaged scenario is a learning-skill increase-learning virtuous cycle with related impacts on work, social and cultural aspects, a more alarming scenario seems to apply to low-skilled individuals who risk to enter a vicious cycle along the line of poor participation-decline in skills-lesser chances to participate in other learning activities, and therefore see the opportunity move further and further away to build an adequate wealth of skills for an effective participation from a work, social and cultural point of view.

[1] As far as Italy is concerned, the group of school-leaving certificates defined as ” low” includes: no certificate or lower than primary-school certificates, primary-school certificates, lower secondary-school certificates and new mandatory schooling certificates, short regional courses (1st level). The group of school-leaving certificates defined as “medium” includes: five-year high-school diplomas, State-run vocational training school certificates, IFTS (Higher Education and Vocational Training Courses) and second level regional courses. The grouping defined as” high” includes: 3-5 or 6-year degrees, diplomas issued by Music Conservatoires, Academies of Fine Arts, Dance Academies, Actor’s or Film Director’s Schools or ISIA (Higher Institutes for Artistic Industries), post-graduate diplomas or post-graduate special studies diplomas (at least 2 years), PhD.

Overview and data processing by Manuela Amendola.